Wartime memories of an evacuee: Trevor Cradduck remembers:

Original pdf can be found here - War memories pdf , or you can read it below.My parents and I lived in Plumstead, South East London at the beginning of World War II. We were located not so very far from Woolwich Arsenal which was a prime target for German bombers. It was hardly surprising then that some of those bombs dropped close to our house. We would take shelter each night in our Anderson shelter that Dad had built in the back garden and emerge to survey the damage in the morning. I think it must have after the second time that Dad found the front door at the top of the stairs he decided that Mum and I needed to be evacuated. He worked for the Southern Railway as a traffic controller but no doubt realized that although his position might be protected his conscription into the armed forces was highly likely.

Waterloo Station had been bombed the night before we were due to leave. My recollection of the events is that of sitting in a car or taxi that was to take Mum and me to Woking to catch a train to the West Country. We finished up in Exeter although I am not at all sure how that came to be our destination. We found ourselves billeted in the front room of a terraced house, sharing with Auntie Lily, who was a friend of my mother’s, and her daughter Brenda. We must have been very cramped and, when the bombing of London eased a few weeks later Auntie Lily and Brenda returned to their home in London.

Bower Hinton

Mum was a chronic asthmatic and it may have been the continual stress or perhaps the location that exacerbated her condition but, whichever it was, she decided to move from Exeter to Bower Hinton which is an extension of the village of Martock in Somerset. Once again, I have no idea how we managed to move there. It was most likely under Mum’s initiative as we finished up living in one of the cottages on Bower Hinton Farm but were really no better off than before. Dad must have been conscripted into the services at about that time and he came to visit. Finding us in a pretty poor condition he vowed to get us settled before he had to report for his “square bashing”. Given that he and Mum were strong Methodists it must have seemed the most appropriate action was to approach the church “elders”. He took me along, rather like the Jehovah’s Witnesses like to have a child along to make their plight more plausible, and he and I walked into Martock’s centre where he began to make enquiries.

The village bakers were Methodists and they directed Dad to call on the Stricklands living at 10 North Street.

10 North Street

Before the war the front room at 10 North Street had been the “home” of the local village telephone exchange but Martock was one of the very first villages to have an automatic exchange installed so here was an elderly couple living in a house which, at that time, had three bedrooms, a front room, a dining room behind and, in an extension (which no longer exists) at the back accommodating a kitchen, a scullery, a laundry space and a storage/work room plus a lavatory. Indeed, this house, unlike many in the area was also blessed with an upstairs bathroom. The Stricklands had already realized that with that amount of space they were easy prey for the billeting officers and were almost obliged to take in some evacuees. Surprisingly, despite its recent history as a telephone exchange #10 had no telephone!

We did not have hot running water anywhere in the house but there was a gas “geyser” water heater for the bath and we were allowed one bath per week with 4 inches of water in the bath. Lighting the geyser was job not to be taken lightly as it could present some interesting challenges. Both the toilet in the upstairs bathroom and the downstairs lavatory were flush toilets whereas many houses in the village still had outdoor privies. In all likelihood the relatively advanced amenities found in #10 were a result of the Strickland brothers being associated with the building trade.

If you have ever seen the movie “Goodnight Mr Tom” starring John Thaw you will have a good idea of Harry Strickland who, with his brother, Fred, were the village carpenters and undertakers. Harry and his wife Ethel became “Uncle” and “Auntie” to me for the rest of the war. They could not have been more hospitable to Mum and me. We were given one of the front bedrooms and Uncle built a small bed for me using spare lumber and chicken wire with a straw filled palliasse as a mattress. Mum had a single bed in the same room so it must have been a bit of a squeeze when Dad did get the rare opportunity to visit before his departure overseas.

The 1901 census shows that Harry Strickland was born in 1872 so he would have been 68 or 69 by the time we descended upon them in 1941. Ethel would, presumably, have been much about the same age. Fred, his brother, was 11 years younger than Harry so was likely the more active of the two in their carpentry and undertakers business. They maintained the business throughout the war because all the younger men had been called up to military service. The business was closed in about 1946 and the buildings sold off to Brooks Garage, next door, where Mum had worked during the war.

In retrospect Harry and Ethel Strickland were pretty brave to take on a young mother with her four year old son at their age and they remained close friends right up until their deaths some years later. Our experience as evacuees was in stark contrast to that which some were obliged to endure although, like us, many enduring friendships also grew out of those difficult years.

Dad conscripted to the RAF

By about the time we moved to Bower Hinton Dad had been conscripted into the RAF and was doing his “square bashing” in Cardiff. Later he was posted to, I believe, Lyneham which is near Chippenham, Wiltshire. There must have been the odd occasion where he was released on a “48-hour” pass and would hitch-hike his way down to Martock and wake Mum by throwing grit up against the bedroom window. I would awake in the morning to find Dad was there, usually only for a day or two before he was obliged to trek back to his RAF station. As an aside I should point out that forces personnel were almost obliged to hitch hike around the country when they had time off and those civilians who did have petrol and were driving vehicles were only too happy to provide rides.

Dad took a navigation course but I think his eyesight precluded him from airborne service. He became a traffic controller which, when you think about it, was the most logical posting he could have had considering that his role on the railway had also been as a traffic controller. Given that most service personnel finished up in jobs totally unrelated to their civilian lives it must have been pure luck that Dad finished up where he did. I do remember him telling us on one occasion that he was appalled when he wrote his navigation exam to see the door at the front of the room open and a blackboard displaying all the answers held up for all to see. It goes to show how desperate the RAF was for navigators but I would not have wanted to be an air crew with such navigators – although, I suppose, the navigators, regardless of their competence, or lack thereof, would have had just as great a desire to get back to base as anyone else in the airplane.

Dad leaves for parts unknown

Not long after his basic training Dad was posted overseas. He did not know where he was going, only that he had to report to a troop ship. He came to visit for his pre-embarkation leave and Mum and I went with him to Taunton to see him off. It must have been hard for them because they did not know where he was going or if they would ever see each other again. Letters were censored so, even if he had learned where they were destined, he could not write and tell – but he did! His ship sailed down around the Horn of Africa and it was not really until that time that they had any real idea of their destination. Anyway, there is a hymn in the Methodist hymn book that tends to describe the world in different verses. Mum and Dad had arranged a code such that, once he had some inkling, he inserted the number of the verse that indicated India or the Far East in his letter to her.

Dad in India

I really do not know where Dad was posted in India. I did try to find out a few years ago by obtaining his service record from the RAF archives in the UK but there is no record of any locations. That would seem to make sense in the context of the secrecy of wartime postings. His service record merely shows that, over the five or so years that he was in the RAF, Dad was promoted from Aircraftsman to Leading Aircraftsman, to Pilot officer, and finally to Flight Lieutenant by the time he was eventually demobilized. Certainly at one time Dad served on the Burmese front. He was in Transport Command and they were dropping supplies to the army (the Chindits) behind the Japanese enemy lines in Burma.

There were a couple of incidents that Dad did tell us about after the war. On one occasion he was flying in a Dakota (a DC3). How he came to be there given that he was on ground staff, not flight crew, remains a mystery. In any event they were to drop a parachute with supplies from the aircraft but when they did so the parachute opened prematurely and caught on the tailplane. This immediately tipped the plane and the pilot reacted quickly by going into a steep bank in an effort to lose the recalcitrant load. Dad found himself on the floor of the aircraft sliding back precariously towards the open door. Fortunately he was able to grab hold of one of the ribs of the airframe and halt his slide to doom. Unlike the load they had dropped he was not wearing a parachute and goodness only know where he would have landed had he been so equipped.

The second incident involved a troop of Ghurkas and demonstrates their incredible discipline. A small troop of Ghurkas arrived on a flight that had been subject to considerable turbulence. When paraded off the aircraft one was found to be missing. The sergeant in charge was questioned as to where was the missing soldier. He reported that the missing man had been very sick as a result of the turbulence and that when he, the sergeant, went to ask “Johnny Pilot” what to do “Johnny Pilot” who, of course was very busy trying to control his aircraft had responded “Oh, chuck the bugger off”, so that is exactly what they had done. Whether the “Johnny Pilot” ever received any reprimand remains unknown but I bet he was very careful with any commands he made after that.

I do know that during his time in India Dad was either stationed at or visited Calcutta, Delhi, Bombay (probably landed and left from there), Kashmir and Rawalpindi, both of which were, at that time, part of India, not Pakistan. The last two places were, I imagine, during vacation since they were far from the Burma front.

My mother’s step brother, Richard Webber, also served in the RAF in India and there was at least one occasion when he and Dad were able to arrange some time together though they were never posted to the same station.

Letters during the war were heavily censored. Although I suspect my parents wrote to one another fairly often we used to receive a batch of letters about once a month. Letters had to be written on special forms that were read by the censors who redacted words, sentences or whole paragraphs. Then the form letters were photographed and microfiched for easier and cheaper transportation. At the destination end they were once more enlarged and forwarded on to the recipient. It was hardly a means for personal or intimate communication and one was always conscious of not writing anything sensitive that would be subject to censorship.

Life in Martock

Mum found a job at the local garage, Brooks on Water Street, as a book keeper/secretary. The garage had a reduced staff in those days and most of their activity was engaged in keeping agriculture machinery or other war related transportation running. Civilian cars were few and far between and petrol was only provided to those for whom it could be soundly justified. The staff in 1941 consisted of the owner, Mr Brooks, the manager, Ben Collings, and several mechanics – Bill Smith, George Tucker, his brother Bert Tucker and Norman Young are the names I remember. Norman might well have been conscripted into the forces except that he was, perhaps too young or important to the war effort where he was. I do not remember the other lads in the photo. They may well have been under military age in 1941 but conscripted later. Note the misspelling of “Cradduck” – a common mistake given that Craddock is the usual spelling. This photo is taken from “Martock Memories – A Hundred Years of Village Life” by Roy Maber who has written several books about Martock history.

I was enrolled in a private school run by a spinster, Miss Avery, located in the lower room of the old Court House close by the Village Church. This building dates from the early 16th century and became a school in 1661 so certainly carries plenty of history. It is now a private residence. I actually started off across the road in “Pattenden” but we moved into the Court House after, perhaps, one term.

Miss Avery had a school of 20 or 25 children ranging in age from 4 (me!) to 14 which was the school leaving age in those days. Since she was the sole teacher the older children were often responsible for teaching the younger ones. Miss Avery was a strict disciplinarian but a great teacher. Soon after I arrived at the school she called me to the front of the classroom and told me that I needed to “pull up my socks”. Keep in mind that boys did not start wearing long trousers until they were 13 or 14 so I calmly bent down and pulled up my socks though I could not understand why they needed pulling up when they were already well up to my knees. Fortunately Miss Avery did not scold me for being cheeky. She must have realized my innocence and probably had a good snigger behind her hand later. That school gave me a great grounding which enabled me to enter a grammar school on our return to London at the end of the war.

Miss Avery lived in East Lambrook, a village some 2.5 miles (4 km) from Martock and she used to cycle into school and back home again every day. On one occasion there was a heavy snow fall but she still managed to turn up at school having donned her Wellington boots and trudged over the fields – a distance that may have been marginally shorter, but I doubt it. Since she had no assistant and no means of communicating to parents that the school would be closed she had little option. Some of the pupils came somewhat longer distances. One girl I recall lived on a farm at Long Load which was probably about 4 miles (6.5 km) each way. I don’t know how she commuted each day but presume she either cycled or walked. It may well have been the latter as I do remember walking home to #10 with her (it was on her way home) and asking her to come in to see the photo that had just arrived of Dad in his officer’s uniform about which I was obviously proud and excited.

At some stage or another I received my first education into the “birds and the bees”. Mum and I were taking a walk one weekend when we came to a gate into a field at the end of Pound Lane beyond which there was a cow evidently in labour. I am sure the farmer would have much preferred to have the calving take place in a barn but this cow seemed to be all on its own. Mum must have decided that this would be a good lesson for me as we stopped and watched the whole thing from the front legs and head appearing to the final delivery and after birth. We watched as the cow cleaned up her offspring and helped it to get to its unsteady feet in order to suckle and gain strength. The other part of the “birds and the bees” came much later.

Methodist Church

Mum and Dad were strong Methodists, having attended and been married at Wesley Hall in Plumstead. It had been natural for Dad to turn to seek the help of the church when he was looking for new accommodations for Mum and me in either late 1940 or early 1941. Given that, it is hardly surprising that we finished up with equally strong Methodists, perhaps even more so than Mum and Dad!

In 1941 the Methodist Church in Martock enjoyed a large congregation. It was a very large building with rooms behind the pulpit and a couple more buildings at the back – a “Mens’ Hall” and another large hall which is where the social facilities for the soldiers was set up in the evenings. (See John Bull and Uncle Sam later.)

The Church also boasted a three manual plus foot pedal organ. (See later reference). Unfortunately the congregation has obviously died off because by 2000 the church was all closed and the front was beginning to be overgrown with weeds. Indeed, there was a sapling growing from between the stones on the front step. Whatever happened to those lovely oak pews and the organ?

Given their strong Methodist background the Stricklands were ardent teetollars. However, before we arrived on the scene they had nursed “Auntie Meg” through her dying days so, one day when there was need for some brandy or such, Mum was despatched upstairs to the Strickland’s bedroom to fetch a bottle that was in the wardrobe, wrapped in newspaper and carefully labelled “Meg’s Medicine”! There are ways of getting around the strictures of the church when needs must.

Each Sunday we would go to church morning, afternoon and, if I did not have school the next day, evenings too. In the mornings the children started off with the adults and then would be shepherded out for Sunday School before the sermon. Given the fire and brimstone nature of the holier than thou local preachers I suspect the Sunday School teachers were only too glad of the excuse to be with us and not stuck with the rest of the congregation. The afternoons were devoted entirely to Sunday School and we were given stamps to stick in a book to record our faithful attendance. The evening services were similar to the morning services except that we children did not escape and were obliged to sit through long boring sermons.

Sad to say, the pattern was much the same when we returned to Plumstead after the war in that my parents attended Wesley Hall morning, afternoon and evening and I was, of course, expected to join them. Mum was one of the Sunday School teachers so my choices were somewhat limited. I did, at one point, rebel and insisted that I stay at home one afternoon, but spending an afternoon on my own at home turned out to be even less appealing than attending Sunday School so my rebellion was short lived.

To give credit where credit is due the congregation at the Martock Methodist Church did embrace the refugees from the war into their midst and did their very best to make us feel at home. There were concerts and outings to keep us occupied even if a picnic on Ham Hill did require that we all walk there and back lugging our picnics with us – a distance of perhaps two miles (4.2 km) each way with a steep climb up Ham Hill included.

Bombing raids

On the whole we were very lucky living in Somerset. We did not have to retire to an air raid shelter each night as did the residents of the large cities. We were still subject to the blackout though. One night I went up to our bedroom to go to bed. I switched on the light and went over to the window to pull down the blind. Before I could even reach the window the front door bell was already ringing. It was the local village Bobby admonishing my mother for the fact that there was a light showing.

There was great excitement when we were bombed on a couple of occasions. Neither instance was serious with, I think, the worst damage being a hay rick that was set on fire. Having said that there was one occasion when a stray bomber flew over the village one summer afternoon. I was with “Uncle” walking back to his workshop next door to the garage where Mum worked when this German bomber flew low over the church and started strafing the village. Uncle shoved me under the handcart he was pushing but I doubt that would have been much protection. Mum, on the other hand, opened the window behind her desk and found herself looking directly at the rear gunner as the plane came over the garage and headed south. Fortunately the mechanics from the garage were quick witted and she was no sooner looking out of the window than she was pulled away and rushed downstairs into one of the pits under a vehicle. I believe a small fire was started in Yandles timber yard but that was quickly extinguished. The closest call was for a couple of elderly ladies sitting in their garden somewhere on Hurst enjoying a cup of tea when a bullet shot past them and into the skirting board of the living room behind them.

Several of the fellows at the garage were volunteer firemen. They were called upon when Exeter and then Plymouth were badly bombed in April 1941. They left on their open fire engine, drove all the way to each of those two cites, fought the fires and then came back, again on the open fire engine, to appear back home so blackened with smoke that they looked like the minstrel boys. To their good fortune, none of them was injured and I guess Martock had no fire emergencies while they were away.

The calling out of the fire brigade was always a source of great interest. As soon as the alarm sounded everyone would run to the street to watch the action. On one occasion one of the village butchers who delivered meat from a trailer behind his car was close to 10 North Street when the alarm sounded. His daughter came tearing down the street on either his or her bike with his uniform on a hanger streaming over her shoulder. It looked as if father and daughter had practised and perfected the transfer as she managed to slip off the bike, hand him his uniform and allow him to proceed in one smooth movement without the bike appearing to stop. He headed off down the street pulling his jacket on as he went; she took over the meat deliveries.

At weekends Mum and I used to go for some long walks along the country lanes and footpaths. On one such occasion we were near Stoke Sub Hamdon (Stoke Under Ham) when Bill Smith and Bert Tucker from the garage appeared taking the fire engine for a test drive…. or so they said! It also happened to be close to my birthday so I suspect this may have been a “set up” because I was allowed to sit up front next to the driver and ring the bell as we drove back into Martock. Not many six or seven year olds actually get to fulfill their wish to ride a fire engine and, in addition, ring the bell.

Martock was also “home” to some Italian Prisoners of War (PoWs). They were evidently trustees as they were housed in the Moat House on Pound Lane, cared for themselves and were not guarded. They wore brown work coveralls with large orange discs on their backs. I am sure the discs were there to distinguish them, not to be used as targets. They assisted the farmers in their fields and farmyards. Ordinarily I would have suspected this might have been in contravention of the Geneva Convention but since they were not engaged in direct war work and had likely volunteered to act as auxiliary farm workers I suppose that was acceptable. For them I am sure it was far better than living in a PoW camp with no activities to keep them occupied. I am not aware that any of them ever attempted to escape and the villagers certainly accepted their presence with equanimity.

Funerals

Uncle and his brother were the village undertakers. It was therefore not uncommon for there to be a knock on the front door early in the morning requesting Uncle to “come and measure Dear Auntie” who had passed away the previous day or during the night. He and Fred would pay a visit to Yandles Timber Yard and make a suitable coffin from solid oak wood with, when they could get them, fancy brass handles. Auntie would prepare suitable dressing for the interior of the coffin. Then they would organize the funeral at the local Parish Church, All Saints. During the war there were no hearses or carriages so the funeral procession would consist of Uncle and his brother donning their funeral “blacks” including top hats with black ribbons and walking in front of the pall bearers who pulled the coffin along on an oak bier – a kind of wooden gurney, with the mourners following. The procession would walk from the deceased’s house to the church with many villagers standing at their front doors to pay their respects.

The bier still survives today and is now used as a coffee table after the Sunday services in the Parish Church.

Somewhere along the way I must have either read Dicken’s “Oliver Twist” or become otherwise aware of the time when Oliver is “employed” to walk in front of funerals. It therefore became my desire to have a black suit and top hat with ribbons down my back so that I, too, could participate in these funerals. Fortunately it was a desire that was short lived.

Village Industry

A number of the smaller village industries were obliged to contribute to the war effort. Martock was well known for its glove factory and I can imagine that gloves were in high demand by the forces. It was a cottage industry so although the main factory was located down the lane behind the White Hart most of the machine work was done by women working their treadle machines in their homes. In the summer it was a common sight to see women with the front doors of their cottages open and busy working on another batch of gloves that were delivered and collected by a young man who was too young for service on his bicycle.

Yandles timber yard was always busy and presumable supplied much needed lumber of various shapes, sizes and lengths. I think it was Paulls who had a small establishment in what now appears to be Vincent Way. I note that they are builders merchants today and that may have been their trade during the war although I thought they were involved in tents and canvas.

Christmases

By Christmas 1944 the war in Europe must have been progressing reasonably well such that people were beginning to relax and make efforts to see life return to normal. By this time I was eight years old so likely asserting myself a little more. Uncle and I caught Wintle’s bus from Martock into Yeovil for, I presume, some Christmas shopping. Late in the afternoon I must have told Uncle to go back to the bus and wait for me there. I am surprised he complied and in this day and age I cannot imagine any adult leaving an eight year old to himself in a “strange” town. It was later reported to me that the next thing Uncle saw as he sat on the bus waiting for me to arrive was a Christmas tree approaching with no one in sight until I climbed on board and it was revealed that I was the carrier. I must have saved my pennies and decided that, at last, we were going to have a tree for Christmas.

Christmas presents were, for obvious reasons, difficult during the war. I was given a Meccano set at one time and I also received what I think was called a Kliptiko set. That may not be the correct name but it was a set of metal tubes that had clips on each end so that they could be used to build scaffolding type structures. Where the metal for such toys came from is a mystery because, at the outset of the war all iron gates and fences plus surplus pots and pans had been collected for the war effort. 10 North Street had originally had an iron gate and a chain across the front garden but these had gone by the time we arrived. Books were the staple present and I collected a number of Rupert the Bear books over those years.

It must have been in 1945 that my mother took me to my first film – Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs. According to Wikipedia this film was first produced in 1937 then re-released in 1945 to raise revenue for the Disney studio during the war. I had seen films previously but they were shown in the open air from the back of a truck that came to the village and were most likely Pathe news or propaganda films extolling the virtues of investing in War Savings Bonds. How to get there from here

Transportation in the ‘40s was, to say the least difficult! I have already noted that service men were often obliged to hitch rides to get home for visits. Furthermore, signposts had been removed in order to hinder the enemy should there have been an invasion. Dad had a pocket edition the Bartholomew Road Atlas that he used to have with him to help him see the roads and railways that he needed to aim for. Having been a railway employee gave him the advantage that he could sometimes hitch a ride on a goods train if there was no passenger train available.

We used to travel into Yeovil, a distance of seven miles, on Wintle’s bus that seemed to run once in the morning and back again in the afternoon. Martock was served by a railway in these pre-Dr Beeching days. The Stricklands had a son, Hedley, living with his wife Carol in Taunton and we went there by train. Hedley Strickland also served in the RAF. Auntie and Uncle had another son, Wilfred, who lived with his wife Kitty in Bridgewater and we went there by train too. The train ran from Yeovil to Taunton so to get to Bridgewater involved a change at either Taunton or Castle Carey. The railway line between Yeovil and Taunton was mostly single track and the running stock consisted of carriages that had no corridors. By implication that also means they did not have toilets either. It was fairly usual for these trains to be held up for one reason or another and on one occasion I desperately needed to “spend a penny”. How does a mother deal with a small boy hopping from one foot to the other who needs a bathroom when there is none available and one can hardly “hide behind a bush”? On this occasion Mum produced a brown paper bag (plastic was unheard of) into which I was able to relieve myself before the bottom dropped out and she was able to throw it out the carriage window.

My cousin Ann was born in February 1943 when her mother, Dora, and father, Leslie Hogger, were living in Batley, Yorkshire. Uncle Les had been transferred up there as he was working for Siemens and their Woolwich factory was either already bombed or was a prime target situated as it was beside the River Thames in Charlton, London. It is, in a way, ironic that he was working for a German company on radar equipment to be used in the war against Germany.

In the summer of 1943 we went to Batley to visit with them and to get there had to travel by train. The trains were, I suppose, few and far between so they were dreadfully crowded. We seemed to spend the whole trip standing in the corridor or sitting on our suitcases and the trip was by no means a short one from Martock up through Bristol, across the Midlands and up into Yorkshire.

Batley is close to Leeds and in a heavy industrial area. Auntie Dora used to wash Ann’s nappies (no disposable diapers!) and hang them on the line outside to dry but, by the time they were dry, they were spotted all over with soot. It is a wonder that Ann did not grow up with a black bum.

John Bull and Uncle Sam

There was a large army camp located north of the railway station in Martock where Stapleton Close is now located which, at the beginning of the war housed British troops. The Methodist congregation used to open the chapel hall to these soldiers and prepare tea and sandwiches for them. I am not sure where on earth the ingredients came from as we were on pretty short rations by that time. One day Mum and Auntie prepared baked potatoes and I gather these were a great hit with one Scots fellow pronouncing to his buddy in a broad Scottish accent “Will ya look a’ tha’, George, wee tatties in their jackets, m’n”.

Later, when the US joined the war, Martock became a base for American soldiers and they used Ashfield House as their HQ. This was cause for some upset among the local residents who, although prepared to accept the presence of the British Tommies, were somewhat less inclined to be hospitable towards these Yanks, some of whom, God forbid, were black! The situation was not made any better by the soldiers who, having “had their way” with some of the local lassies posted their used condoms through the letter box of the local chemist close by The George. I suppose we can at least take comfort from the fact that they were engaging in safe sex and may well have been avoiding the awkward situation that could have arisen when the local lads returned from the war to find some “surprises” awaiting them.

Various events took place to try to brighten up an otherwise sombre atmosphere as the war progressed and Britain seemed to be no closer to a victory. One event was a talent concert with a fancy dress parade to raise money for War Savings Bonds. Mum and Auntie got going with their needles and thread to create a costume for me showing me as John Bull on my right side and Uncle Sam on the left. The photo does not really do the costume justice but I have been unable to enhance it much more. The britches were made by inverting my small scale carpenter’s apron and folding it in half. The shirt and jacket are half Union Jack, half Stars and Stripes. The hat, too, was half and half. As you can imagine Mum and Auntie were very proud of their handiwork when I came away with the first prize!

Little Goodie Two Shoes – NOT!

I suppose, like most small boys of that age, I managed to get myself into enough scrapes and troubles to try the patience of any parent. One of my more minor transgressions was to try to sneak a biscuit out of the biscuit barrel. Auntie’s biscuit barrel was a china model cottage, the roof of which constituted the lid. That gabled roof would ring like a bell if you were not really, really careful lifting and replacing it! I don’t think I ever managed to perfect the art of pinching a biscuit when no one was listening. Suffice to say, when she died Auntie bequeathed that china biscuit barrel to me. I warrant she had a smile on her face when she wrote that into her will.

There are only three or four more serious episodes that stand out in my mind. Whether that is because I was punished more severely or for some other reason, who knows? Seven years of bad luck?

At some time or another I must have read a book or listened to a radio program that involved the use of a mirror to reflect the sun’s rays. One summer evening I crept from my bed to the bathroom at the back of the house facing west and, of course, the evening sun. I took my mother’s hand mirror and started to flash the reflection on the roof and wall of the barn that closed off the end of the backyard. Mum and the Stricklands must have been enjoying the evening sun in the backyard and this bright reflection moving about all over the place could hardly have gone unnoticed. In any case, I heard Mum exclaim, realized I had been caught, and was about to receive the sharp end of her tongue so dropped the mirror and scampered back to my bed where I feigned sleep ready to blame one of those two elusive characters “Not me” and “I don’t know”. Now, dropping the mirror would have been bad enough, but I had the stupidity to drop it out of the window so that it landed on the sloping corrugated steel roof of the kitchen below, slid down the roof and landed with a clatter at Mum’s feet. It did not survive but we seemed to survive the following seven years without the proverbial bad luck.

The case of the warm pearls

I must have either dreamt up my naughtiness when I was put to bed or just could not sleep. It would have been a dark night with the blackout in place when I wanted to read so lit the bedside candle. Upon hearing my mother as she came up the stairs to bed I popped the lit candle into the cupboard beside her bed and went to “sleep”.

Mum wore a pearl necklace and when she went to put the necklace on the next morning they were not cold to the touch. Indeed they were positively warm. When she opened the cupboard upon which they had been sitting overnight to investigate there was the candle burned down to as stub and a nicely charred scar above it. It was pure luck that we did not have a fire.

Bell tents are for sliding down

One summer, perhaps 1942 or ’43, my mother’s old office colleague, Lily, who had been evacuated with us to Exeter came to stay for several weeks with her daughter, Brenda. They stayed in a large house on East Street that was owned by one of the more important and financially comfortable Martock families. It is even possible that Lily was engaged to house sit while the family was away.

I don’t know why but there was a large canvas bell tent erected on the lawn. A bell tent is similar in shape to a wigwam but has a central pole. Now, if you run hard enough and jump high enough it is possible to slide down the side of a bell tent. Brenda and I found that out without any hesitation whatsoever. We enjoyed the pastime but the bell tent did not! Sooner rather than later, one or the other of us made our last run at the tent, bounced as high up as we could but landed inside the tent itself having torn a hole in our slide. Poor Auntie Lily could hardly do much else than try to pull the two sides of the tear together with needle and thread. I doubt it would have even been possible to obtain a piece of canvas to make a patch during the war. Certainly the tent was never the same again and any further sliding was out of the question.

Grapes are for eating

That same summer and at the same house where Lily and Brenda were staying there was a grapevine in the greenhouse. The grapes were nearing perfection so were extraordinarily tempting to two small kids. We were told that we could have one grape each per day off the bunch hanging closest to the door. That, unfortunately, was not sufficient for Brenda. Instead of taking grapes off bunches close to their base she sampled the single grape at the tip of each bunch.

When the house owners returned from their holiday the man of the house was livid as he had been harbouring dreams of making a shilling or two by selling his greenhouse produce but, so far as he was concerned, every bunch had been spoiled by the absence of the grape at the tip of the bunch. I received a darned good scolding but was in the fortunate position of being genuinely innocent on this occasion. I imagine Brenda did not get off as lightly.

Food in the Forties

Food was, of course, strictly rationed throughout the war years and even for sometime after the war. The following table of food rations is copied from Wikipedia:The average standard rations during the Second World War are as follows. Quantities are per week.

| Item | Maximum level | Minimum level | Rations (April 1945) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bacon and Ham | 8 oz (227 g) | 4 oz (113 g) | 4 oz (113 g) |

| Sugar | 16 oz (454 g) | 8 oz (227 g) | 8 oz (227 g) |

| Loose Tea | 4 oz (113 g) | 2 oz (57 g) | 2 oz (57 g) |

| Meat | 1s. 2d. | 1s | 1s. 2d. |

| Cheese | 8 oz (227 g) | 1 oz (28 g) | 2 oz (57 g)

Vegetarians were allowed an extra 3 oz (85 g) cheese |

| Preserves | 1 lb (0.45 kg) per month 2 lb (0.91 kg) marmalade |

8 oz (227 g) per month | 2 lb (0.91 kg) marmalade or 1 lb (0.45 kg) preserve or 1 lb (0.45 kg) sugar |

| Butter | 8 oz (227 g) | 2 oz (57 g) | 2 oz (57 g) |

| Margarine | 12 oz (340 g) | 4 oz (113 g) | 4 oz (113 g) |

| Lard | 3 oz (85 g) | 2 oz (57 g) | 2 oz (57 g) |

| Sweets | 16 oz (454 g) per month | 8 oz (227 g) per month | 12 oz (340 g) per month |

Eggs were rationed and "allocated to ordinary consumers as available"; in 1944 thirty allocations of one egg each were made. Children and some invalids were allowed three a week; expectant mothers two on each allocation.

- 1 egg per week or 1 packet (makes 12 "eggs") of egg powder per month (vegetarians were allowed two eggs)

- plus, 24 “points” for four weeks for tinned and dried food.

Arrangements were made for vegetarians so that their rations of meat were substituted by other goods.

Milk was supplied at 3 imp pt (1.7l) each week for priority to expectant mothers and children under 5; 3+1/2 imp pt (3.3l) for those under 18; children unable to attend school 5 imp pt (2.8l), certain invalids up to 14 imp pt (8.0l). Each consumer got one tin of milk powder (equal to 8 imperial pints (4,500 ml; 150 US fl oz)) every 8 weeks.

In the above table most rations are given in terms of quantity – weight or volume. One exception is meat which is given a 1s 2d per week. That is the amount that could be spent on meat each week and is equivalent to about 5p per week in today’s decimal currency although inflation would increase its value many times over. The reason for rationing based on price was, of course, because meat can vary so much in price. I don’t know if we had very much liver and onions but I do recall that we tried tripe and onions on one occasion. I can happily report that it was on only one occasion. Much later, after the war, we did have whale meat which was acceptable. Despite the small meat ration we seemed to be able to manage a small piece of roast beef most Sundays after morning chapel.

We used to pick up bread from the local bakers just down the street (now “The Old Bakery” next to the P&M Store) and milk was delivered into a jug set on the front door step each day. Given my age it would appear that our house was able to buy a little more milk than would have been the case otherwise.

Food was not the only rationed item at that time. We were also restricted to one bath per week with no more than 4” (10 cm) of water in the bath. In order to get in two baths per week Mum would follow me once I had bathed.

Uncle’s brother, Uncle Fred to me, initially lived on the south side of East Street and owned a field on the opposite side of the street where he kept chickens and geese. I don’t know what situation prevailed with respect to the eggs. I imagine they had to be reported to the authorities but I suspect that quite a number must have been “broken” in the collection process! I do know that the butter and sugar rations made cooking very difficult and, due to the low sugar content I developed an eczema for which the doctor prescribed glucose which was not rationed and could therefore be obtained.

One of Uncle Fred’s geese was named Simon and, whenever we went into the field, it seemed that Simon took great offence to my presence such that I became pretty scared of him. You can imagine I was pleased when Simon became our Christmas dinner one year. The plucked and drawn bird was taken to the bakery on Christmas morning and, along with many other birds, was baked in the bread oven. One of the Strickland’s sons, Wilfred, visiting with his wife Kitty from Bridgewater, and I went to the bakery later in the day. He carried the cooked goose home on a large platter while I followed close behind with a jug full of the goose fat. That was quite a feast not just because it was war time but because Simon, my nemesis, was finally eradicated.

It must have been fairly early on that Uncle Fred, who was a widower when we arrived at 10 North Street, married again. He married a woman who lived in a bungalow at the junction of Foldhill Lane and Ash Lane. The house had quite a large garden so it became our vegetable garden. Uncle and I would walk up there and dig the ground over in the Spring and harvest the produce later in the summer. Uncle also had a greenhouse in the backyard where he proudly grew tomatoes with plenty of very smelly horse manure to help the process along.

Many of the villagers would also help with the harvest of wheat or barley. The farmer would go round the field with a horse drawn cutter that also tied the wheat into bundles, or sheathes. We would follow behind and gather the sheathes into stooks to dry ready for threshing. All of this sounds as if we were there to help the short-handed farmers which may well have been the case, but there was also another ulterior motive. As the field of grain got smaller and smaller the rabbits that had migrated towards the centre in fear of the cutting machine would bolt out to take refuge in the hedge. If you were really quick and nimble you could catch a rabbit and augment your meat ration.

The local grocery store in Martock (now the P&M Store) was owned and run by the Bennett family. Since Auntie did the shopping Mum was not a regular at Bennetts, or any of the other grocery stores, but one day Mr Bennett came to her at the garage with a tin of ham – a rare commodity in those days. Mum at first refused since she did not have sufficient food coupons and felt she was being bribed for some special service by the garage. Mr Bennett assured that this was not the case. He had received a shipment but he dare not release any of it to his regular customers for fear they would get into a fight over it. Mum accepted and we had ham.

Mum was also subject to a fraud when she was offered some sheets. Given that our bed linen had been well and truly worn and that she had already halved them and turned them hem to hem to put the thinner parts towards the sides of the bed she readily accepted the offer. Not so very long afterwards the police came to the door with a US Army officer in tow. They asked if she had purchased any sheets lately and when shown them they quickly revealed that the turned in hems actually had “Property of the US Army” printed on them. She had to turn them over and, of course, lost whatever she had paid for them. I might add that Mum was conned once again when she purchased a watch for me many years later. She did not seem to be able to detect when something had “fallen off the back of a lorry”. On this latter occasion she was not caught as a receiver of stolen goods.

D-Day, 1944

June 6th, 1944 was D-Day or Operation Overlord when British, American and Canadian forces invaded Normandy. June 6th was actually a Tuesday. We knew something was definitely happening the previous weekend. On the Sunday Mum and I had walked over Bearley Bridge, up Foldhill Lane, and out to the Fosse Way – now the A303. There was a huge convoy of army vehicles heading east and it just never ended while we stood there and wondered. There was even a cobbler sitting on the back of one truck still mending boots as the convoy went on its way.

Then on the Tuesday we really knew what was going on as the sky was filled with airplanes, many of them towing gliders. It was like a swarm of bees in the sky. I think everyone must have heaved a sigh of relief that finally something was happening and it appeared to be something over which we had control.

The six o’clock news (on the radio) was always listened to with great concentration by the adults. It was preceded by Children’s Hour with Uncle Mac who signed off every night with “Good night, children, everywhere”. The radio was, of course, a battery radio. It had a very large high voltage battery made up of multiple dry cells connected in series. Then there was a wet battery, or accumulator, that was used to drive the elements in the valves. That battery had to be taken to the store every so often to be recharged and, since no one wanted to miss the latest news, there was a spare accumulator so that they could be swapped. There was just the one radio in the house and it, you may rest assured, was tuned to the BBC Home Service – just about the only radio station there was anyway. In the front room we had a wind up record player and a stock of vinyl records for “entertainment” although there was also a piano which Mum played occasionally.

I was also given piano lessons by Miss Bennett, the grocer’s daughter, but have to admit that I was not very keen on practising which led to some tears when I was threatened with a cane if I did not get into the front room and do my scales. Mum must have realized it was a waste of money so my lessons were stopped. In retrospect, I wish now that I had been encouraged, perhaps not driven, to become more proficient. However, for a small boy of six or seven I imagine there are far more interesting things to do than learning to appreciate music! Dad also played the piano and he took great delight in “having a go” on the three manual organ with foot pedals that was in the Methodist Chapel in Martock on the rare occasions when he had the chance.

I graduate from tricycle to bicycle

Before we were evacuated my parents must have bought me a tricycle, perhaps for my third birthday. How that tricycle got to Martock I do not know. Certainly I do have a clear memory of riding it from Bower Hinton Farm to 10 North Street with the front handlebar basket full of wax candles when we moved in with the Stricklands. It had not been in Exeter so my guess is that Dad brought it down when he visited Bower Hinton and found us in poor circumstances.

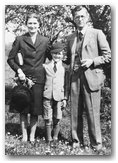

The photo shows Mum and me just past Brooks Garage (you can see the petrol pump hose) outside the wall of the Strickland’s carpentry business. That wall is now gone as the carpentry shop became part of Brooks Garage.

By the time late 1944 or early 1945 had rolled around I was far too big for this tricycle which, I suspect, had been sold to some other lucky child in the village. In any case Mum made some enquiries and was able to purchase a second hand adult bicycle for me. It was very much the upright with rod brakes, no gears and, because of the wartime black out was painted black – totally black, including the handlebars. It was also way too big for me so Uncle fastened wooden blocks that must have been about an inch thick to the pedals so that I could ride it. Mum then, very patiently, and surely for her, very much out of breath then hung on to the saddle as I tried to learn to ride. No training wheels in those days!

That bike survived a number of years and was even ridden on a cycle tour around Somerset, Dorset, Devon and Cornwall in the summer of 1948.

In the Spring of 1945 we must have returned to Plumstead, but I cannot recall why. Perhaps it was in order to check up on the house at 47 Highmead prior to moving back later that year. What is memorable for me is the fact that my mother and someone else took me up to London in order to “see the sights”. I suspect they may well have been more interested in seeing the bomb damage or perhaps what damage the bombing had had on the routine sight seeing route. We went first to Tower Bridge, then the Tower of London and from there walked towards St Paul’s Cathedral. It must have been April 17th as we found ourselves in a large crowd gathered to witness the many dignitaries arriving at the cathedral for President Roosevelt’s Memorial Service. In the space of one hour we must have seen more European monarchy and other high ranking officials than I could ever expect to see in a whole life time. Many of the European monarchy had found refuge in Britain during the war years. Among the dignitaries, of course, were King George VI, the Queen and Winston Churchill. After the parade had passed we went on to go down The Strand, into Trafalgar Square, down The Mall to Buckingham Palace. Since Easter in 1945 fell on April 23rd we probably went to London during what would have been my school break. We obviously returned to Martock as I certainly finished my school year there.

V-E Day, 1945

Eventually, to every ones’ relief, the war in Europe was over. V-E Day was a few weeks later on May 8th, 1945. During the war the ringing of church bells was strictly forbidden. One of the fellows at the garage, who was also a fireman, vowed that as soon as victory was declared he would be the first to ring the bell in the Market House. You can just make it out at the far end of the roof in that little gable arch in the sketch. Bill Smith made good on his word BUT, he pulled the rope, but only the once, with such gusto that he pulled the bell over the top and it jammed in the arch in which it hung. So with one clang of the bell, Bill’s celebration came to a sad end and it was a number of years before the bell was restored to its proper position.

Dad returns from India

Although the war in Europe was yet not over, and certainly not in the Far East, Dad was posted back to the UK in early 1945. At least hostilities in the Middle East had calmed a little as they sailed home through the Suez Canal and the Mediterranean Sea. They had sailed out to India around the Horn of Africa and Cape Town. Although hostilities may well have been less dangerous I do remember Dad complaining that the whole way through the Mediterranean Sea the ship was firing depth charges as they could not be sure that German U-boats were not patrolling the area. A few months later Mum’s step-brother, Dick, was able to fly home but, given the aircraft in those days, it must have involved multiple hops and some very long flights.

According to his service records, once back in the UK Dad was posted first to Lyneham in Wiltshire in April of 1945, then moved to Merryfield, Somerset which was not very far from Martock just three weeks later. Then, barely 5 weeks after that, he was moved to Watchfield which is, again, in Wiltshire and was therefore a little further away from Martock. He was moved yet again three months after that to Bassingbourn in Cambridgeshire – further away again, but closer to London. He was eventually demobilized from the RAF at the rank of Flight Lieutenant on the 2nd of February, 1946. What I did not realize until I had checked these records is that he was then part of the RAF reserve until he was finally released in February of 1954. That must have been when I inherited his air force great coat as a winter coat for my student days at the University of Bristol.

Dad was pretty unsettled following the war. This, I suppose, was understandable. He had travelled far overseas, had been in a fairly responsible position and had risen in the ranks to be a commissioned officer. It must have been a bit of a let down to come back to traffic control on the Southern Railway after those experiences. I know that at one time he even enquired about emigrating to Rhodesia (now Zimbabwe). Given the subsequent conditions in that country thank goodness we did not leave Britain. I believe he also enquired of the, then, BOAC about the possibility of becoming a civil aircraft traffic controller but nothing came of that. I am sure the same loss of status must have been suffered by a number of services personnel in those postwar years. It must have been far worse for those who were injured or, like one of Dad’s old Scouting buddies, been Japanese prisoners of war who were treated so badly.

Back home in Plumstead and Timbercroft School

We returned to 47 Highmead in the summer of 1945 after V-E Day and I started at the local school, Timbercroft Lane School, that following September. Unlike my class mates at Timbercroft whose education had been frequently interrupted and had also been in large classes I was well ahead of them as a result of my schooling by Miss Avery. The consequent result was that I was thoroughly bored in Mr Hersey's class at Timbercroft Lane and my marks were probably beginning to show it.

I do recall that when Christmas 1945 came along we had some tangerines distributed to the school and Mr Hersey demonstrated how to peel it in one go thereby avoiding a gross mess in the classroom. It was a good example of “Simon Says” although I doubt that Mr Hersey’s name was “Simon”.

There was a green grocery store at the top of Highmead on Swingate Lane. On the last day of 1945 a shipment of bananas arrived at Bristol Docks. They were rationed and available only to children under 18 and expectant mothers. One morning early in January word quickly spread among neighbours that some of these bananas had arrived at the green grocers. My mother made sure she was in the queue and was so delighted that she brought me a single banana delivered in the playground before school started that morning. I had never seen a banana before and when it came to playtime I could not figure out how to peel the darned thing. I imagine I eventually bit into the stem and managed to peel it but my frustration managed to attract a small gathering of my classmates who were equally intrigued.

In the years following the war things remained in short supply. Many things were still on ration – sweets did not come off ration until 1951. Electrical appliances were beginning to make their appearance in the home and my mother desperately wanted an upright Hoover vacuum cleaner. The only way they could afford to buy one was on “the never-never”. Other than mortgaging for houses it was unheard of to buy anything on credit unless you were well established and could afford to run a tab at the local butchers, the bakers, or the pub. It was a major step for my parents to subject themselves to weekly payments for a vacuum cleaner and they agonized over taking this step. This is something we take for granted in these days of credit cards.

Dad was very proud of the fact that he had taught himself to drive while in India. He had “borrowed” the airfield’s ambulance and managed to grind through the gears on the runways and taxiways. One day, in the Officer’s mess, the camp commander came in and enquired if anyone there could drive. Not being shy in coming forward, Dad readily claimed that he could. It was then that he learned he was to take visiting Squadron Leader so-and-so to the railway station. Dad managed to get there all in one piece by staying in first gear the whole way. Only on the way back did he even dare to try second gear in the camp commander’s car!

With this singular achievement Dad was able to obtain a driver’s licence upon his release from the air force and in 1947 he bought his first car – a second hand black Morris 8 with the registration number AUE 483. We had nowhere to park it at 47 Highmead. There are no garages on that road even today so he rented a garage up close to Timbercroft Lane School on Irwin Ave. One night a car horn started to sound and it sounded somewhat familiar so when it did not stop Dad donned his clothes and trotted up to the garage to find that AUE had an electrical short and was letting everyone in the neighbourhood know. That was easily solved by disconnecting the battery until it happened once again sometime later and, rather than having his rental of the garage revoked, Dad did get the problem fixed properly.

Dad never did take any driving lessons nor was he ever subjected to a driving test……. And it showed! A member of the Advanced Institute of Motoring he was NOT. He did try to give Mum driving lessons but she was extremely nervous and soon gave up in order to become a highly accomplished, but unlicenced, back seat driver. To give her credit, Mum recognized that there was no way I was going to learn to drive properly if Dad taught me. When I turned 17 (1953) she paid for me to take driving lessons at the British School of Motoring in Bromley and I am glad to report that I passed my test on the first attempt.

Entry exam to Roan School for Boys

In early 1946 my mother noticed an advertisement on the front page of the weekly Kentish Times announcing pre-11 plus entrance exams for the Roan School for Boys (now the John Roan School) in Greenwich. At first she dismissed the idea of me taking any such exam because she figured there was no way she and Dad could afford the fees but then she noticed the small print stating that fees were no longer payable at the Roan. Armed with this advertisement she went to see the Head at Timbercroft to seek permission for me to take the exam. He opined that he didn't see much hope for me but it might serve as good experience for the 11-plus which I would have to write the next year anyway.

Mum and I duly took the bus to Blackheath and walked down Maze Hill to the school on the appointed afternoon. There seemed to be masses of other boys, some even arriving in chauffeur driven cars – this, in 1946! There were some boys with rulers and T-squares plus rows of pens in their jacket pockets. I know I felt out of place and I think Mum rather wished she had not been so insistent. We had to write Maths and English exams. I distinctly remember there was one question – “Give the feminine equivalent of the following “– and one was “Duke”. I know I wrote Dukess only to discover later that it was Duchess. I figured I was certainly doomed for failure. It was a day for celebration when the results arrived and I had been accepted into the school.

This, of course, meant the acquisition of a school uniform at a time when clothing was still rationed. We had to catch the bus all the way to Lewisham and purchase the uniform as Cheeseman’s on Lewisham High Street. Needless to say, I was proud as punch and even wore my uniform, including beanie cap, on holiday that summer.

School uniform

Our school uniform consisted of a single breasted green blazer, grey flannel shorts (or long trousers in upper years), long grey socks with green bands at the top, grey flannel shirts (later white), a school tie that was green with black and silver strips and a green school cap. The blazer had a white stag, or roan’s, head embroidered on the pocket and the cap had a metal stag, or roan’s, head badge. Because of clothes rationing the blazer was regarded as optional but highly recommended. The cap had to be worn at all times when traveling to and from school. Yes, I still wore a school cap at the age of 19 when I was in the 3rd Year Sixth Form!

The whole school was divided into Houses – Nelson, Drake, Rodney, Raleigh, Collingwood, Blake, Grenville and Wolfe. In 1946 I was placed in Wolfe House and consequently sported a yellow enamelled button in the top of my school cap. In 1948 or thereabouts the increase in school activities meant that there were insufficient boys in each of eight Houses to compete effectively so we were consolidated into just four Houses – Drake, Nelson, Rodney and Wolfe.

Pride in the school uniform waned sometime around the age of 15 and many of us opted to wear sports jackets. I have no doubt that this was frowned upon by the senior staff, but many of the lads would have been leaving school at the age of 16 and would need something other than a school blazer for work so I suspect that our actions were condoned rather than cause an uproar over dress codes.

By the time we reached the Sixth Form our pride of school had returned and we senior boys made a special deputation to the Head requesting that we be allowed to wear double breasted black blazers with the full school crest in all its resplendent colour on the pocket; a request that was duly granted probably because the staff realized that such blazers would be more appropriate when we attended interviews for jobs or university.

Those of us who became School Prefects in our last one or two years at the school wore caps that were green but had black panels front and back edged with silver cord. I have to concede that, by that time, I wore my cap only when the rules absolutely required me to do so. By that time my journey to school took me on a train first, followed by a bus ride. The Phys-ed teacher, Mr Westmorland, lived in the next road to us so made the same journey but he turned a blind eye to my capless head. However, when we had to catch the bus I would have to don my cap since there was a certainty that there would be more junior boys on the bus and I, as Prefect, would be obliged to admonish them if they were not wearing their caps. My cap also came off when I got off the bus on my way home in the afternoons!

School uniform also extended to sports – black shorts for soccer and PT, house coloured shirts for soccer, singlets (vests) for running and PT, white shirts for cricket and, of course, the right footwear; either soccer boots or plimsolls (sneakers) for running and PT. Then of course there were the soccer socks and shin pads. All this clothing made for an expensive outing to Cheesemans. Fortunately my mother was ever resourceful and very adept with a needle and thread so, when I grew too big for one blazer and had to move up a size, instead of paying Cheesemans for an embroidered blazer, she would purchase a cheaper one and use the first pocket badge as a pattern to embroider a new one for the new blazer.

Holiday in Margate

Perhaps as a celebration of our reunion as a family and even of my success in gaining entrance to the Roan we went for a summer holiday in 1946 to Margate, Kent. We stayed in a B&B but, since food was still rationed, the breakfasts were decidedly lacking in imagination. We were served a routine cup of tea accompanied by maybe three thin slices of fried potato and a piece of toast – eggs and bacon, NOT. Fortunately there was a café not very far up the road to which the guests, with tummies rumbling and mouths grumbling, would repair to augment the meagre breakfast we had just been served.

Trevor D. Cradduck

2014-02-18