George Parsons, Flax and the Parrett Works

Written by Sandy Buchanan Sunday, 25 September 2011 15:42

This article is taken from an excellent book “From Field to Factory, Flax and Hemp in Somerset’s History from 1750” written by C. A. (Sandy) Buchanan, published by SIAS (the Somerset Industrial Archaeologicy Society), 2008. It is a wonderful description of the mechanisation of what had until then been a cottage industry. Flax and hemp grow well in our climate and clay soils, and Sandy’s book is a wonderful evocation of an exciting Industrial Revolution in an area often not thought to have had one! We strongly commend this book, at only £9. To get a copy, go to a proper book shop, or contact www.sias.me.uk The following is an extract from the section on the flamboyant entrepreneur George Parsons, followed by an appraisal of his legacy to Martock, the magnificent and largely intact industrial complex he built at the Parrett Works in the 1850s.

1at extract: George Parsons (pp 34-8)

1at extract: George Parsons (pp 34-8)

George Parsons, who started to manufacture goods from flax and hemp in Somerset before 1g50, came from a very different background to those entrepreneurs already mentioned. He was born in 1807 at west Stour in Dorset and started his working life as a gentleman farmer, being an early recruit to the English Agricultural Society, later to be known as the Royal Agricultural Society of England. He settled at New cross Farm as tenant and steward to Lord Portman, and from there married a Miss Gale of Glastonbury in St. John's parish church on the 27th March 1839. He soon began designing machinery to increase output and improve ways of performing- the routine tasks of agriculture. He patented a “Portable Roof for agricultural and other purposes" in lg43 and, in conjunction with the engineer, Richard Clyburn of Uley, near Dursley in Gloucestershire, he patented a machine for "cleaning and crushing vegetable substances'. This patent suggested that the machine could be used for threshing grain crops, crushing apples and linseed, and most significantly for this study, the scutching of flax. clyburn subsequently helped parsons to pioduce a threshing machine at West Lambrook. By the early1850s T. D. Acland, an authority on agricultural practice in Somerset at that time, concluded that New Cross Farm should "be viewed rather as the central factory of a large property than as a model farm building for ordinary purposes". Not only the preliminary processes necessary for the production of flax goods, but a twine walk was established there by 1854.

By that time, Parsons was already looking for space to develop his engineering aspirations and in December 1853 he had purchased Cary's Mill, an unoccupied corn mill on the River Parrett between South Petherton and Martock. In the same month the Bristol & Exeter Railway's broad gauge extension from Durston to Hendford was operating through Martock. In February 1854 a destructive fire broke out in the flax stamping room at New Cross Farm. The Bridgwater Times described the sad event, "An iron foundry for themanufacture of agricultural implements has lately been erected, and it is supposed a spark from the chimney fell on some flan, an immense quantity of which was spread in the surrounding buildings, and ignited it....Most of the machinery was destroyed, being fused, £1,000 worth of flax was destroyed," and there was also significant loss of livestock.

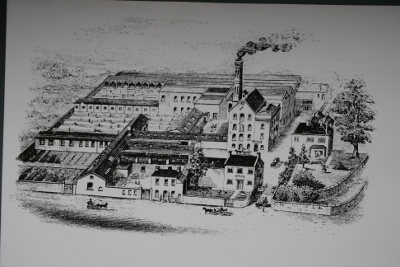

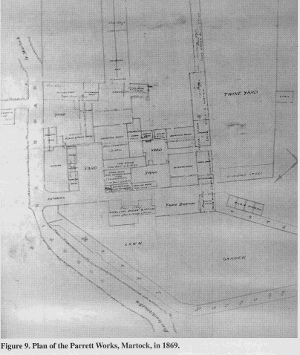

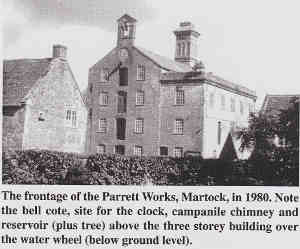

This disaster no doubt speeded Parson's move to Cary's Mill and helps to explain why it was rebuilt with regard to the fire-proofing principles advocated by contemporaries. The original footprint was retained but the new factory to be known as The Parrett Works, was erected to a height of three storeys in stone, some of which came from Hele Manor in South Petherton, including the mullioned windows.30 The building was adorned by a clock and a belfry. According to local tradition, the bell came from the recently demolished prison in Ilchester. Both of these items indicated the transition to factory work and the necessary time-discipline which accompanied it. More significantly, in an industry plagued by fires, the building adopted some of the fire-proofing recommendations of another engineer, William Fairbairn, in his Report on the Construction of Fireproof Buildings of 1844. Not only were the pillars supporting the upper floors made of cast iron, but the slates were fixed to wrought iron bars resting on iron roof trusses. Access to the upper floors was by iron staircases built round a cast iron newel which carried water, pumped by the main water wheel to a reservoir at roof height, from which it could be accessed at each floor level in the event of a fire. Thankfully, this whole system has survived to the present day, making the building one of the most interesting industrial monuments in the south west of England. Interest is increased by the survival of the original iron, low breast, suspension water wheel, and the elegant Ham stone campanile-style chimney. Elsewhere on the site are one and two storey buildings which housed the preparatory stages of flax production and rope and twine walks. One of the latter served for many years as a cow byre but is now in a derelict state.

The weir across the Parrett, with its quaint sluice-watchman's building, channeled the mill leat into the site, past the retting tanks and supplied water to a second water wheel of l2feet diameter and 9 feet 9 inches width, before it reached the bigger wheel already mentioned.

These premises add up to what was a state-of-the-art complex designed to produce spun yarn, woven cloth and sacking, twine and rope. Adjacent to it there was an engineering workshop with lathes, a foundry and blacksmith's forge, in a single storey factory. By 1865 Parsons was able to secure financial backing to launch the West of England Engineering & Coker Canvas Co. Ltd., with an initial capital of f100,000 in f50 shares.

(The clock has now been lovingly replaced)

This must have been one of the first businesses in Somerset to take advantage of the recent Limited Liability Act of 1862, which limited the liability of each shareholder to the amount of money they had personally invested in a business. This was a very significant change in the business legislation of the country which encouraged those of relatively modest means to invest in enterprises worth thousands of pounds, without risking their financial security.

Photo: the remarkable feature of this staircase is that the central newel column is a hollow water pipe. The huge water reservoir on the roof above supplied water to it, which could then be used in case of fire. The Memorandum of Association for the new company shows that there were seven main shareholders at the launch, subscribing more thanfI2,000. Joseph Milsom, a merchant of Reading, bought 20 shares and also of that town, a draper, George Dunlop, bought 60 shares and Charles Holbrook, another draper, 10 shares. Charles Barnard, described as a gentleman of Newbury also in Berkshire, bought 30 shares. The three remaining shareholders resided in Somerset. Thomas Harris Smith of Midsomer Norton, a brewer, bought 20 shares and George Bullock Murly, a solicitor from Langport bought five. The biggest shareholder was Parsons himself who had 100 shares, based on the valuation of the machinery he owned in the Parrett Works. He was appointed Managing Director but did not have a vote on the Board of Directors. The company indicates how new capital was brought into the area, in this case from Reading and Newbury and it was presumably these shareholders who decided to close the business down when it failed to deliver the return on their investments which had been anticipated. The final winding up meeting was held on the 23rd December 1870 but the decision to go into liquidation had been taken at an Extraordittary General Meeting of the company on 16th August and 6th September 1868 held in Reading.

The reasons for this action may be found in the general economic situation, as a number of other local businesses went the same way at this time, but the original objectives of the West of England Engineering and Coker Canvas Company Ltd may give a better clue. These objectives were set down in the Memorandum of Association as, "The purchasing and selling or otherwise disposing of Flax, Hemp, Jute, Tow and all other Materials, Articles and things used in the manufacture of Ropes, Yarns, Twine, Thread, Canvas, Sail-Cloth, Sails, Sacks, Bags , Tents and Tarpaulins and of every other description of Cloth or Covering, whether linen, woollen, or cotton, or any other material; and also the spinning, bleaching, manufacturing, purchasing, selling, exporting, or otherwise disposing of Ropes, Yarns, Twine, Thread, Canvas, Sail-Cloth, Sails, Sacks, Bags, Tents and Tarpaulins ..........and also the construction, building, manufactu drg, repairing, purchasing, selling, exporting, lending on hire or otherwise disposing of other Engines, Machines, Implements, Tools etc.." These catch-all phrases suggest a business not properly focused but reflecting the interests of its Managing Director, who was primarily an engineer with a secondary interest in processing and manufacturing flax, hemp and jute. It may be that the relatively recent decision to start manufacturing sailcloth may have brought the whole business down. It was reported in 1862 that "Mr. Parsons has recently added to his works the manufacture of sailcloth."34 There was already machine weaving as well as hand loom weaving at the Parrett Works in 1865 when a new weaving shed for 25 power looms for sailcloth, a dyeing house and drying room were introduced. 3s Demand for flaxen sailcloth was declining after the prosperity generated by the American Civil War came to an end. A financial crisis in 1866, the resumption of massive supplies of raw cotton from the ravaged plantations of the defeated Confederacy after the end of hostilities in 1865, ild the falling demand for canvas and sailcloth as steam power steadily replaced that of wind for the nation's mercantile marine and Royal Navy, all contributed to the general malaise which affected the flax and hemp-based industries of Somerset. The production of sailcolth stopped at the Parrett Works in 1868 and Messrs Fuller, Horsey, Son & Co. were advertising the sale of the flax preparing and spinning machines, together with 14 Power Looms, "a complete Bleaching Apparatus" and much of the engineering machinery in November 1869.

In 1873 Parsons emigrated to New Zealand to join his sons and died there three years later. His principal interest to this study lies in the significant heritage which he left behind. The physical remains at the Parrett Works have already been outlined and will be considered further in the last chapter. His engineering achievements have survived in the area through the enterprise of William Sparrow, who established the Somerset Wheel and Waggon Company at Bower Hinton, and of William Sibley who bought the engineering workshops at the Parrett Works and continued to manufacture iron and steel machinery and equipment for a regional market. So far as flax and hemp are concerned, Parsons initially sold this business to his brother, Henry who lived at Haselbury Plucknett. Also in that parish was George Hedgecombe Smith who operated a rope and twine manufacturing business. Henry Parsons leased his part of the Parrett works to Smith in 1875. Presumably he eventually bought the works which were to continue in production until after the Second World War when, in 195I, the twine and cordage business was transferred to J. B. Gould & Sons at West Coker. The matting business was transferred to Crewkerne Textiles.